Comparison Introduction

Here are a few of the high-level design decisions that we think make Samza a bit different from other stream processing projects.

The Stream Model

Streams are the input and output to Samza jobs. Samza has a very strong model of a stream—it is more than just a simple message exchange mechanism. A stream in Samza is a partitioned, ordered-per-partition, replayable, multi-subscriber, lossless sequence of messages. Streams are not just inputs and outputs to the system, but also buffers that isolate processing stages from each other.

This stronger model requires persistence, fault-tolerance, and buffering in the stream implementation, but it has several benefits.

First, delays in a downstream processing stage cannot block an upstream stage. A Samza job can stop consuming for a few minutes, or even a few hours (perhaps because of a bad deploy, or a long-running computation) without having any effect on upstream jobs. This makes Samza suitable for large deployments, such as processing all data flows in a large company: isolation between jobs is essential when they are written, owned, and run by different teams in different code bases with varying SLAs.

This is motivated by our experience building analogous offline processing pipelines in Hadoop. In Hadoop the processing stages are MapReduce jobs, and the output of a processing stage is a directory of files on HDFS. The input to the next processing stage is simply the files produced by the earlier stage. We have found that this strong isolation between stages makes it possible to have hundreds of loosely coupled jobs, maintained by different teams, that comprise an offline processing ecosystem. Our goal is to replicate this kind of rich ecosystem in a near-real-time setting.

The second benefit of this stronger model is that all stages are multi-subscriber. In practical terms this means that if one person adds a set of processing flows that create output data streams, others can see the output, consume it, and build on it, without introducing any coupling of code between the jobs. As a happy side-effect, this makes debugging flows easy, as you can manually inspect the output of any stage.

Finally, this strong stream model greatly simplifies the implementation of features in the Samza framework. Each job need only be concerned with its own inputs and outputs, and in the case of a fault, each job can be recovered and restarted independently. There is no need for central control over the entire dataflow graph.

The tradeoff we need to make for this stronger stream model is that messages are written to disk. We are willing to make this tradeoff because MapReduce and HDFS have shown that durable storage can offer very high read and write throughput, and almost limitless disk space. This observation is the foundation of Kafka, which allows hundreds of MB/sec of replicated throughput, and many TB of disk space per node. When used this way, disk throughput often isn’t the bottleneck.

MapReduce is sometimes criticized for writing to disk more than necessary. However, this criticism applies less to stream processing: batch processing like MapReduce often is used for processing large historical collections of data in a short period of time (e.g. query a month of data in ten minutes), whereas stream processing mostly needs to keep up with the steady-state flow of data (process 10 minutes worth of data in 10 minutes). This means that the raw throughput requirements for stream processing are, generally, orders of magnitude lower than for batch processing.

State

Only the very simplest stream processing problems are stateless (i.e. can process one message at a time, independently of all other messages). Many stream processing applications require a job to maintain some state. For example:

- If you want to know how many events have been seen for a particular user ID, you need to keep a counter for each user ID.

- If you want to know how many distinct users visit your site per day, you need to keep a set of all user IDs for which you’ve seen at least one event today.

- If you want to join two streams (for example, if you want to determine the click-through rate of adverts by joining a stream of ad impression events with a stream of ad click events) you need to store the event from one stream until you receive the corresponding event from the other stream.

- If you want to augment events with some information from a database (for example, extending a page-view event with some information about the user who viewed the page), the job needs to access the current state of that database.

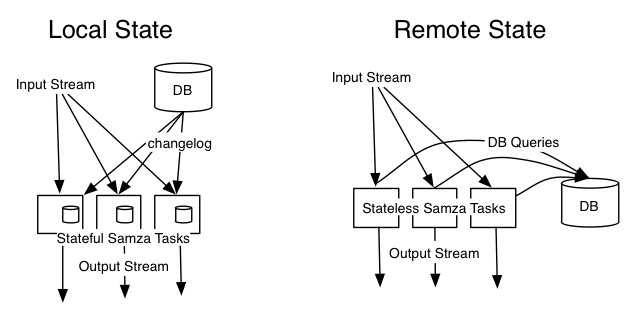

Some kinds of state, such as counters, could be kept in-memory in the tasks, but then that state would be lost if the job is restarted. Alternatively, you can keep the state in a remote database, but performance can become unacceptable if you need to perform a database query for every message you process. Kafka can easily handle 100k-500k messages/sec per node (depending on message size), but throughput for queries against a remote key-value store tend to be closer to 1-5k requests per second — two orders of magnitude slower.

In Samza, we have put particular effort into supporting high-performance, reliable state. The key is to keep state local to each node (so that queries don’t need to go over the network), and to make it robust to machine failures by replicating state changes to another stream.

This approach is especially interesting when combined with database change capture. Take the example above, where you have a stream of page-view events including the ID of the user who viewed the page, and you want to augment the events with more information about that user. At first glance, it looks as though you have no choice but to query the user database to look up every user ID you see (perhaps with some caching). With Samza, we can do better.

Change capture means that every time some data changes in your database, you get an event telling you what changed. If you have that stream of change events, going all the way back to when the database was created, you can reconstruct the entire contents of the database by replaying the stream. That changelog stream can also be used as input to a Samza job.

Now you can write a Samza job that takes both the page-view event and the changelog as inputs. You make sure that they are partitioned on the same key (e.g. user ID). Every time a changelog event comes in, you write the updated user information to the task’s local storage. Every time a page-view event comes in, you read the current information about that user from local storage. That way, you can keep all the state local to a task, and never need to query a remote database.

In effect, you now have a replica of the main database, broken into small partitions that are on the same machines as the Samza tasks. Database writes still need to go to the main database, but when you need to read from the database in order to process a message from the input stream, you can just consult the task’s local state.

This approach is not only much faster than querying a remote database, it is also much better for operations. If you are processing a high-volume stream with Samza, and making a remote query for every message, you can easily overwhelm the database with requests and affect other services using the same database. By contrast, when a task uses local state, it is isolated from everything else, so it cannot accidentally bring down other services.

Partitioned local state is not always appropriate, and not required — nothing in Samza prevents calls to external databases. If you cannot produce a feed of changes from your database, or you need to rely on logic that exists only in a remote service, then it may be more convenient to call a remote service from your Samza job. But if you want to use local state, it works out of the box.

Execution Framework

One final decision we made was to not build a custom distributed execution system in Samza. Instead, execution is pluggable, and currently completely handled by YARN. This has two benefits.

The first benefit is practical: there is another team of smart people working on the execution framework. YARN is developing at a rapid pace, and already supports a rich set of features around resource quotas and security. This allows you to control what portion of the cluster is allocated to which users and groups, and also control the resource utilization on individual nodes (CPU, memory, etc) via cgroups. YARN is run at massive scale to support Hadoop and will likely become an ubiquitous layer. Since Samza runs entirely through YARN, there are no separate daemons or masters to run beyond the YARN cluster itself. In other words, if you already have Kafka and YARN, you don’t need to install anything in order to run Samza jobs.

Secondly, our integration with YARN is completely componentized. It exists in a separate package, and the main Samza framework does not depend on it at build time. This means that YARN can be replaced with other virtualization frameworks — in particular, we are interested in adding direct AWS integration. Many companies run in AWS which is itself a virtualization framework, which for Samza’s purposes is equivalent to YARN: it allows you to create and destroy virtual “container” machines and guarantees fixed resources for these containers. Since stream processing jobs are long-running, it is a bit silly to run a YARN cluster inside AWS and then schedule individual jobs within this cluster. Instead, a more sensible approach would be to directly allocate a set of EC2 instances for your jobs.

We think there will be a lot of innovation both in open source virtualization frameworks like Mesos and YARN and in commercial cloud providers like Amazon, so it makes sense to integrate with them.