State Management

One of the more interesting features of Samza is stateful stream processing. Tasks can store and query data through APIs provided by Samza. That data is stored on the same machine as the stream task; compared to connecting over the network to a remote database, Samza’s local state allows you to read and write large amounts of data with better performance. Samza replicates this state across multiple machines for fault-tolerance (described in detail below).

Some stream processing jobs don’t require state: if you only need to transform one message at a time, or filter out messages based on some condition, your job can be simple. Every call to your task’s process method handles one incoming message, and each message is independent of all the other messages.

However, being able to maintain state opens up many possibilities for sophisticated stream processing jobs: joining input streams, grouping messages and aggregating groups of messages. By analogy to SQL, the select and where clauses of a query are usually stateless, but join, group by and aggregation functions like sum and count require state. Samza doesn’t yet provide a higher-level SQL-like language, but it does provide lower-level primitives that you can use to implement streaming aggregation and joins.

Common use cases for stateful processing

First, let’s look at some simple examples of stateful stream processing that might be seen in the backend of a consumer website. Later in this page we’ll discuss how to implement these applications using Samza’s built-in key-value storage capabilities.

Windowed aggregation

Example: Counting the number of page views for each user per hour

In this case, your state typically consists of a number of counters which are incremented when a message is processed. The aggregation is typically limited to a time window (e.g. 1 minute, 1 hour, 1 day) so that you can observe changes of activity over time. This kind of windowed processing is common for ranking and relevance, detecting “trending topics”, as well as real-time reporting and monitoring.

The simplest implementation keeps this state in memory (e.g. a hash map in the task instances), and writes it to a database or output stream at the end of every time window. However, you need to consider what happens when a container fails and your in-memory state is lost. You might be able to restore it by processing all the messages in the current window again, but that might take a long time if the window covers a long period of time. Samza can speed up this recovery by making the state fault-tolerant rather than trying to recompute it.

Table-table join

Example: Join a table of user profiles to a table of user settings by user_id and emit the joined stream

You might wonder: does it make sense to join two tables in a stream processing system? It does if your database can supply a log of all the changes in the database. There is a duality between a database and a changelog stream: you can publish every data change to a stream, and if you consume the entire stream from beginning to end, you can reconstruct the entire contents of the database. Samza is designed for data processing jobs that follow this philosophy.

If you have changelog streams for several database tables, you can write a stream processing job which keeps the latest state of each table in a local key-value store, where you can access it much faster than by making queries to the original database. Now, whenever data in one table changes, you can join it with the latest data for the same key in the other table, and output the joined result.

There are several real-life examples of data normalization which essentially work in this way:

- E-commerce companies like Amazon and EBay need to import feeds of merchandise from merchants, normalize them by product, and present products with all the associated merchants and pricing information.

- Web search requires building a crawler which creates essentially a table of web page contents and joins on all the relevance attributes such as click-through ratio or pagerank.

- Social networks take feeds of user-entered text and need to normalize out entities such as companies, schools, and skills.

Each of these use cases is a massively complex data normalization problem that can be thought of as constructing a materialized view over many input tables. Samza can help implement such data processing pipelines robustly.

Stream-table join

Example: Augment a stream of page view events with the user’s ZIP code (perhaps to allow aggregation by zip code in a later stage)

Joining side-information to a real-time feed is a classic use for stream processing. It’s particularly common in advertising, relevance ranking, fraud detection and other domains. Activity events such as page views generally only include a small number of attributes, such as the ID of the viewer and the viewed items, but not detailed attributes of the viewer and the viewed items, such as the ZIP code of the user. If you want to aggregate the stream by attributes of the viewer or the viewed items, you need to join with the users table or the items table respectively.

In data warehouse terminology, you can think of the raw event stream as rows in the central fact table, which needs to be joined with dimension tables so that you can use attributes of the dimensions in your analysis.

Stream-stream join

Example: Join a stream of ad clicks to a stream of ad impressions (to link the information on when the ad was shown to the information on when it was clicked)

A stream join is useful for “nearly aligned” streams, where you expect to receive related events on several input streams, and you want to combine them into a single output event. You cannot rely on the events arriving at the stream processor at the same time, but you can set a maximum period of time over which you allow the events to be spread out.

In order to perform a join between streams, your job needs to buffer events for the time window over which you want to join. For short time windows, you can do this in memory (at the risk of losing events if the machine fails). You can also use Samza’s state store to buffer events, which supports buffering more messages than you can fit in memory.

More

There are many variations of joins and aggregations, but most are essentially variations and combinations of the above patterns.

Approaches to managing task state

So how do systems support this kind of stateful processing? We’ll lead in by describing what we have seen in other stream processing systems, and then describe what Samza does.

In-memory state with checkpointing

A simple approach, common in academic stream processing systems, is to periodically save the task’s entire in-memory data to durable storage. This approach works well if the in-memory state consists of only a few values. However, you have to store the complete task state on each checkpoint, which becomes increasingly expensive as task state grows. Unfortunately, many non-trivial use cases for joins and aggregation have large amounts of state — often many gigabytes. This makes full dumps of the state impractical.

Some academic systems produce diffs in addition to full checkpoints, which are smaller if only some of the state has changed since the last checkpoint. Storm’s Trident abstraction similarly keeps an in-memory cache of state, and periodically writes any changes to a remote store such as Cassandra. However, this optimization only helps if most of the state remains unchanged. In some use cases, such as stream joins, it is normal to have a lot of churn in the state, so this technique essentially degrades to making a remote database request for every message (see below).

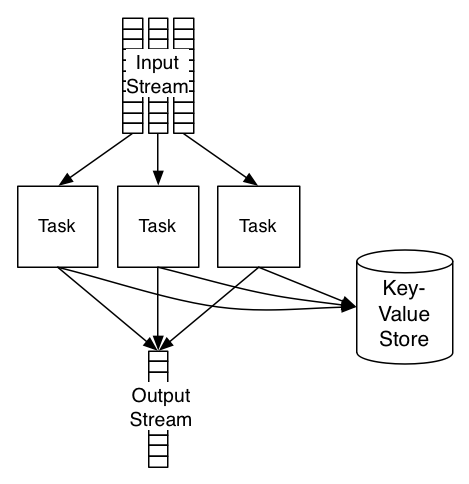

Using an external store

Another common pattern for stateful processing is to store the state in an external database or key-value store. Conventional database replication can be used to make that database fault-tolerant. The architecture looks something like this:

Samza allows this style of processing — there is nothing to stop you querying a remote database or service within your job. However, there are a few reasons why a remote database can be problematic for stateful stream processing:

- Performance: Making database queries over a network is slow and expensive. A Kafka stream can deliver hundreds of thousands or even millions of messages per second per CPU core to a stream processor, but if you need to make a remote request for every message you process, your throughput is likely to drop by 2-3 orders of magnitude. You can somewhat mitigate this with careful caching of reads and batching of writes, but then you’re back to the problems of checkpointing, discussed above.

- Isolation: If your database or service also serves requests to users, it can be dangerous to use the same database with a stream processor. A scalable stream processing system can run with very high throughput, and easily generates a huge amount of load (for example when catching up on a queue backlog). If you’re not very careful, you may cause a denial-of-service attack on your own database, and cause problems for interactive requests from users.

- Query Capabilities: Many scalable databases expose very limited query interfaces (e.g. only supporting simple key-value lookups), because the equivalent of a “full table scan” or rich traversal would be too expensive. Stream processes are often less latency-sensitive, so richer query capabilities would be more feasible.

- Correctness: When a stream processor fails and needs to be restarted, how is the database state made consistent with the processing task? For this purpose, some frameworks such as Storm attach metadata to database entries, but it needs to be handled carefully, otherwise the stream process generates incorrect output.

- Reprocessing: Sometimes it can be useful to re-run a stream process on a large amount of historical data, e.g. after updating your processing task’s code. However, the issues above make this impractical for jobs that make external queries.

Local state in Samza

Samza allows tasks to maintain state in a way that is different from the approaches described above:

- The state is stored on disk, so the job can maintain more state than would fit in memory.

- It is stored on the same machine as the processing task, to avoid the performance problems of making database queries over the network.

- Each job has its own datastore, to avoid the isolation problems of a shared database (if you make an expensive query, it affects only the current task, nobody else).

- Different storage engines can be plugged in, enabling rich query capabilities.

- The state is continuously replicated, enabling fault tolerance without the problems of checkpointing large amounts of state.

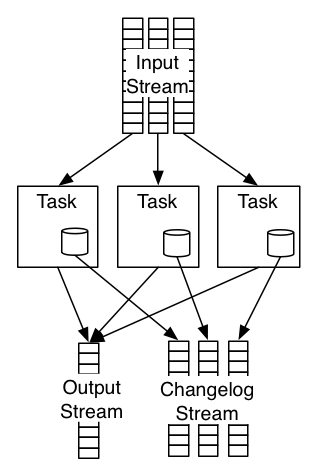

Imagine you take a remote database, partition it to match the number of tasks in the stream processing job, and co-locate each partition with its task. The result looks like this:

If a machine fails, all the tasks running on that machine and their database partitions are lost. In order to make them highly available, all writes to the database partition are replicated to a durable changelog (typically Kafka). Now, when a machine fails, we can restart the tasks on another machine, and consume this changelog in order to restore the contents of the database partition.

Note that each task only has access to its own database partition, not to any other task’s partition. This is important: when you scale out your job by giving it more computing resources, Samza needs to move tasks from one machine to another. By giving each task its own state, tasks can be relocated without affecting the job’s operation. If necessary, you can repartition your streams so that all messages for a particular database partition are routed to the same task instance.

Log compaction runs in the background on the changelog topic, and ensures that the changelog does not grow indefinitely. If you overwrite the same value in the store many times, log compaction keeps only the most recent value, and throws away any old values in the log. If you delete an item from the store, log compaction also removes it from the log. With the right tuning, the changelog is not much bigger than the database itself.

With this architecture, Samza allows tasks to maintain large amounts of fault-tolerant state, at a performance that is almost as good as a pure in-memory implementation. There are just a few limitations:

- If you have some data that you want to share between tasks (across partition boundaries), you need to go to some additional effort to repartition and distribute the data. Each task will need its own copy of the data, so this may use more space overall.

- When a container is restarted, it can take some time to restore the data in all of its state partitions. The time depends on the amount of data, the storage engine, your access patterns, and other factors. As a rule of thumb, 50 MB/sec is a reasonable restore time to expect.

Nothing prevents you from using an external database if you want to, but for many use cases, Samza’s local state is a powerful tool for enabling stateful stream processing.

Key-value storage

Any storage engine can be plugged into Samza, as described below. Out of the box, Samza ships with a key-value store implementation that is built on LevelDB using a JNI API.

LevelDB has several nice properties. Its memory allocation is outside of the Java heap, which makes it more memory-efficient and less prone to garbage collection pauses than a Java-based storage engine. It is very fast for small datasets that fit in memory; datasets larger than memory are slower but still possible. It is log-structured, allowing very fast writes. It also includes support for block compression, which helps to reduce I/O and memory usage.

Samza includes an additional in-memory caching layer in front of LevelDB, which avoids the cost of deserialization for frequently-accessed objects and batches writes. If the same key is updated multiple times in quick succession, the batching coalesces those updates into a single write. The writes are flushed to the changelog when a task commits.

To use a key-value store in your job, add the following to your job config:

# Use the key-value store implementation for a store called "my-store"

stores.my-store.factory=org.apache.samza.storage.kv.KeyValueStorageEngineFactory

# Use the Kafka topic "my-store-changelog" as the changelog stream for this store.

# This enables automatic recovery of the store after a failure. If you don't

# configure this, no changelog stream will be generated.

stores.my-store.changelog=kafka.my-store-changelog

# Encode keys and values in the store as UTF-8 strings.

serializers.registry.string.class=org.apache.samza.serializers.StringSerdeFactory

stores.my-store.key.serde=string

stores.my-store.msg.serde=string

See the serialization section for more information on the serde options.

Here is a simple example that writes every incoming message to the store:

public class MyStatefulTask implements StreamTask, InitableTask {

private KeyValueStore<String, String> store;

public void init(Config config, TaskContext context) {

this.store = (KeyValueStore<String, String>) context.getStore("my-store");

}

public void process(IncomingMessageEnvelope envelope,

MessageCollector collector,

TaskCoordinator coordinator) {

store.put((String) envelope.getKey(), (String) envelope.getMessage());

}

}

Here is the complete key-value store API:

public interface KeyValueStore<K, V> {

V get(K key);

void put(K key, V value);

void putAll(List<Entry<K,V>> entries);

void delete(K key);

KeyValueIterator<K,V> range(K from, K to);

KeyValueIterator<K,V> all();

}

Additional configuration properties for the key-value store are documented in the configuration reference.

Implementing common use cases with the key-value store

Earlier in this section we discussed some example use cases for stateful stream processing. Let’s look at how each of these could be implemented using a key-value storage engine such as Samza’s LevelDB.

Windowed aggregation

Example: Counting the number of page views for each user per hour

Implementation: You need two processing stages.

- The first one re-partitions the input data by user ID, so that all the events for a particular user are routed to the same stream task. If the input stream is already partitioned by user ID, you can skip this.

- The second stage does the counting, using a key-value store that maps a user ID to the running count. For each new event, the job reads the current count for the appropriate user from the store, increments it, and writes it back. When the window is complete (e.g. at the end of an hour), the job iterates over the contents of the store and emits the aggregates to an output stream.

Note that this job effectively pauses at the hour mark to output its results. This is totally fine for Samza, as scanning over the contents of the key-value store is quite fast. The input stream is buffered while the job is doing this hourly work.

Table-table join

Example: Join a table of user profiles to a table of user settings by user_id and emit the joined stream

Implementation: The job subscribes to the change streams for the user profiles database and the user settings database, both partitioned by user_id. The job keeps a key-value store keyed by user_id, which contains the latest profile record and the latest settings record for each user_id. When a new event comes in from either stream, the job looks up the current value in its store, updates the appropriate fields (depending on whether it was a profile update or a settings update), and writes back the new joined record to the store. The changelog of the store doubles as the output stream of the task.

Table-stream join

Example: Augment a stream of page view events with the user’s ZIP code (perhaps to allow aggregation by zip code in a later stage)

Implementation: The job subscribes to the stream of user profile updates and the stream of page view events. Both streams must be partitioned by user_id. The job maintains a key-value store where the key is the user_id and the value is the user’s ZIP code. Every time the job receives a profile update, it extracts the user’s new ZIP code from the profile update and writes it to the store. Every time it receives a page view event, it reads the zip code for that user from the store, and emits the page view event with an added ZIP code field.

If the next stage needs to aggregate by ZIP code, the ZIP code can be used as the partitioning key of the job’s output stream. That ensures that all the events for the same ZIP code are sent to the same stream partition.

Stream-stream join

Example: Join a stream of ad clicks to a stream of ad impressions (to link the information on when the ad was shown to the information on when it was clicked)

In this example we assume that each impression of an ad has a unique identifier, e.g. a UUID, and that the same identifier is included in both the impression and the click events. This identifier is used as the join key.

Implementation: Partition the ad click and ad impression streams by the impression ID or user ID (assuming that two events with the same impression ID always have the same user ID). The task keeps two stores, one containing click events and one containing impression events, using the impression ID as key for both stores. When the job receives a click event, it looks for the corresponding impression in the impression store, and vice versa. If a match is found, the joined pair is emitted and the entry is deleted. If no match is found, the event is written to the appropriate store. Periodically the job scans over both stores and deletes any old events that were not matched within the time window of the join.

Other storage engines

Samza’s fault-tolerance mechanism (sending a local store’s writes to a replicated changelog) is completely decoupled from the storage engine’s data structures and query APIs. While a key-value storage engine is good for general-purpose processing, you can easily add your own storage engines for other types of queries by implementing the StorageEngine interface. Samza’s model is especially amenable to embedded storage engines, which run as a library in the same process as the stream task.

Some ideas for other storage engines that could be useful: a persistent heap (for running top-N queries), approximate algorithms such as bloom filters and hyperloglog, or full-text indexes such as Lucene. (Patches accepted!)

Fault tolerance semantics with state

As discussed in the section on checkpointing, Samza currently only supports at-least-once delivery guarantees in the presence of failure (this is sometimes referred to as “guaranteed delivery”). This means that if a task fails, no messages are lost, but some messages may be redelivered.

For many of the stateful processing use cases discussed above, this is not a problem: if the effect of a message on state is idempotent, it is safe for the same message to be processed more than once. For example, if the store contains the ZIP code for each user, then processing the same profile update twice has no effect, because the duplicate update does not change the ZIP code.

However, for non-idempotent operations such as counting, at-least-once delivery guarantees can give incorrect results. If a Samza task fails and is restarted, it may double-count some messages that were processed shortly before the failure. We are planning to address this limitation in a future release of Samza.